Alchemy in the Marathon's Evolution

Tradition vs. Innovation in an age old competition

This post is dedicated to my good friend Gibson and his organization Time To Compete, A non-profit dedicated to bettering the lives of young adults battling cancer through the power of community. He and Time to Compete have been a big source of inspiration for me and provided me with much needed motivation during my NYC Marathon experience.

Tradition and scientific innovation are two diametrically opposed ideas, yet in the constantly evolving world of sports, they can’t help but be inextricably linked. Over the years, various sports have implemented bans on certain substances and equipment to maintain fair competition. Steroids are the classic examples of performance enhancers that are prohibited across sports/leagues, simi In 1981, adhesives like Stickum were prohibited in the NFL to prevent making footballs too easy to catch, in 2010 full-body Polyurethane swim suits were banned in professional swimming due to a surge in swimmers setting world records, heck even today certain baseball bats are considered "illegal" in the MLB—the list goes on. At the same time sports and the athletes competing in them have changed drastically over the last century; from enhancements in equipment, facilities, and nutrition, to even entirely new rules. In sport when the raison d'etre is human achievement, how does one balance innovation with traditional human performance?

The marathon is without a doubt one of sport’s most demanding feats. People die every year (about one in every 150,000 runners), it requires tremendous training (elite athletes run 100-190 miles a week), and as an achievement just 0.01% of the world's population completes one each year. Despite its difficulty, world records in the competition are being broken every year and it feels like more people are running them than ever before. Are humans just getting faster every year? Are more people getting good enough at running to complete a marathon? Or is there there more than meets the eye?

In the most recent Building Something Old I dove into another antiquated industry, printing/book publishing, as seen in Tyler Cowen’s Marginal Revolution. Today, I explore how innovation has impacted human achievement in the marathon.

A Brief History of The Marathon

Marathon lore dates back to 490BC when the Athenian courier Pheidippides ran 22 miles from the site of the battle of Marathon to Athens with a message of Victory. After completing this journey it is said he shortly after collapsed and died. Despite this ancient fable, the first “modern” marathon didn’t take place until ~2500 years later. Initially, the race came in the form of a 40km (24.85 miles) run at the inaugural modern Olympic games in Athens in 1896. The fastest time for the 40km race was 2:58:50. A year later, the Boston Marathon was created and shortly after the 1904 St Louis Olympics would hold its own Marathon— a race so disastrous that it threatened the existence of the competition in future Games.

Despite the hesitation to continue it, the 1908 Olympics in London not only continued the competition, but actually extended it. Initially fixed at 26 miles, the Queen of England made a late request to move the start back to the East Lawn of Windsor Castle, so that “the race could be seen by the royal children in their nursery.” And just like that, the the 26 mile race became, 26.2 and the modern marathon was born. Queen Alexandra was FTK.

Old Word Running

"I do not think the marathon will be included in the program, and I personally am opposed to it," - James Sullivan, the director of the 1904 Games

The conditions at the 1904 St Louis Olympic Games consisted of the following:

Some runners competing barefoot

Dusty, unpaved roads that were so difficult to run on that the dust inhaled over the course of the race was responsible for ripping the stomach linings of runners

Runners in dress shirt, slacks, leather street shoes, and even a beret

The winning runner was high on a toxic cocktail that contained rat poison, egg white, and brandy. He was fully hallucinating by the end. He also reportedly lost eight pounds during the race.

Only 14 men out of 32 managed to cross the finish line that day.

Fastest finish: 3:28 for 25 miles, which would be a 3:38 minute finish (assuming the same average pace) in todays 26.2 mile distance.

The 1904 St Louis Olympics was by no means the standard of the Marathon running of yesteryear, however imagine this happening in the Olympics today. Impossible.

Modern World Running

In 2023, things are a little different. In the 2023 Chicago Marathon Kelvin Kiptum became the first man to run a sub-2:01 marathon in an officially sanctioned competition. A world-record time of 2:00:35.

During the 2022 INEOS 1:59 Challenge, an unofficial marathon, Eliud Kipchoge became the first human on record to break the two-hour barrier for the marathon, completing 26.2 miles in just 1:59:40:2. That comes out to an average mile time of 4 minutes and 33 seconds. For even the fastest of runners, that is effectively an all out sprint at 100% effort, for the entirety of the 26.2 mile race. Insane.

In addition to records of human achievement being beat left and right, more people are running marathons than ever before in history. Strava reported that the share of runners who raced in marathons on its platform nearly doubled in 2022. The NYC Marathon organization, NYRR, received more than 153,000 applications for the 2023 NYC marathon, the second-highest number of applications in marathon history (only behind 2020). Nearly a century ago the 26.2 mile race that we now know as the marathon did not even formally exist, now over 1.1 million people run a marathon a year, globally.

Innovation In Running

First came rubber soles, then came synthetic tracks, now we have Garmin watches, Strava, and super shoes.

In the 1950’s Keds were making kids “run faster, jump higher, and win more often”. Today, innovation has led to the most elite runners being faster than anyone else in history (increasing performance) while also elevating a greater number of people to run marathons (increasing access).

In the lens of performance, during the 1904 Olympic games the fastest finish would have been a 3:38 finish in todays 26.2 mile distance. This Olympic gold medal wouldn’t even be considered a “good” men’s marathon finish today, which is commonly be defined as a 3:34:56 race. For context I ran a 3:34 marathon in my first ever race this past year and I sit at a desk all day. Even in 1908, the fastest marathon finish at the Olympics was a 2:55:18.4. Although an order of magnitude faster than the 1904 race, in today’s terms this runner likely would not have even qualified to run in the Boston Marathon, which has 22,000+ people make it every year. The TLDR is we are running the marathon faster today than ever before.

Running is already one of the most democratized sports and is accessible, in theory, for nearly everyone, absent of innovation. Where my interest in accessibility comes into play is it has become easier to run a marathon today than ever before in history. Innovations in marathon running have attracted greater numbers of runners and non-runners alike to partake in the Herculian, 26.2 mile challenge.

Below are some of the most notable recent innovations in marathon running.

Super Shoes

“Super shoes” were first introduced by Nike in 2016 with the release of the Vapor Fly. The defining features of the shoes that make them oh so super are 1) a thick yet incredibly light foam sole and 2) a curved carbon plate base. The carbon plate acts as an external recoil device which gives runners even greater propulsion when in stride and the thick foam sole reduces the muscular demand while also returning energy stored in the shoe. Broadly, the category of “Super Shoes” provide runners with more energetic efficiency, as less energy is lost with each step. This means runners are able to go faster for longer distances.

“Studies have found that runners can see a one to three percent increase in speed wearing the shoes — and the faster the pace, the bigger gains.” - via WaPo

A one to three percent increase increase in speed over the course of 26.2 miles results in faster finishes by way of minutes. When world records are determined on a scale of seconds, this matters. A lot.

In 2023, most major manufacturers have their own version of a Super Shoe, the Nike Vaporfly ($260) + The Nike Alphafly ($285), the Hoka Rocket X2 ($250), and Adidas Adizero Adios Pro Evo1 ($500). Nike’s early Super Shoe dominance has been apparent in the numbers. In 2019 Runners wearing the Nike Vaporfly shoes took 31 of 36 podium positions at all major marathons. In terms of world records, there have been five broken since 2018, all in super shoes and 4/5 being in Nikes. This stat excludes Kipchoge’s sub two hour finish in the INEOS 1:59 Challenge, as it was not an officially sanctioned marathon, but he also ran in Nikes.

Men’s Marathon World Records in Super Shoes:

2018 – Eliud Kipchoge – 2:01:39 – Nike Zoom VaporFly Next% prototype

2022 – Eliud Kipchoge – 2:01:09 – Nike Air Zoom Alphafly Next% 2

2023 – Kelvin Kiptum – 2:00:35 – Nike Air Zoom Alphafly Next% 3

Women’s Marathon World Records in Super Shoes:

2019 – Brigid Kosgei – 2:14:04 – Nike Zoom VaporFly Next

2023 – Tigst Assefa – 2:11:53 – Adidas AdiZero Adios Pro Evo 1

*To note prior to Kosgei breaking the record in 2019, the Women’s marathon world record had not been changed for 16 years.

In the lens of the two types of innovation (increasing access and/or performance) Super shoes have had an impact on the latter. They have played a role in making the most elite runners, even better. The jury is still out on their effect on average runners, but an abt quote from kinesiology researcher and pro-runner summarizes their impact:

"So for two athletes of equal ability on race day, the one with the shoes is going to beat the one without the shoes." - Geoff Burns

Wearables

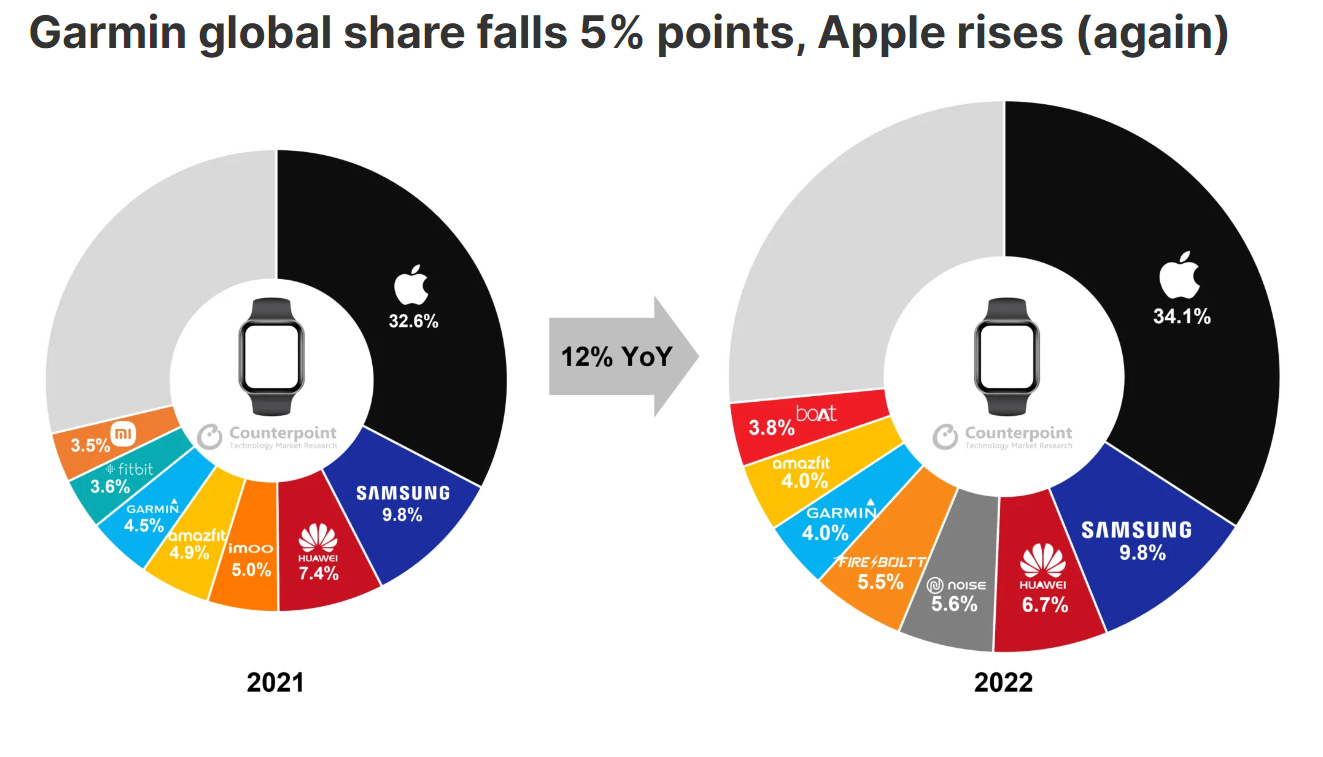

Garmin has been the gold standard for long distance runners looking for precision, accuracy, running specific features, and long battery life. The devices have aided in the trainings of marathoners across the world—providing accurate pace keeping, interval training assistance, and even making race predictions.

Despite this, Apple watches continue to win the game of mass market distribution. Why? Ultimately, it is function of integration—an apple watch can be easily integrated into other parts of your life ie: can receive texts, take phone calls, go through your photos, even check your credit card statement. The power of connecting your watch with your iPhone and Mac does go a long way.

There is no strong argument that using wearables positively impacts running performance, so given the innovation question, wearables fall into the increasing access bucket. Broadly, they have shown an ability to increase physical activity levels amongst wearers. Garmin watches have aided avid runners with further training support and the Apple Watch, given its mass appeal, has done the same, but more importantly encouraged sedentary people to become more active. Running a marathon as an average person is something that happens gradually, then all of a sudden. In my view, an Apple Watch can act as a gateway device to running a marathon. Initially it is harmless— you are just closing your rings and getting your daily steps in...right? Wrong. Next thing you know you start running a couple miles a week. One thing leads to another and now you and a couple friends are signed up for a half marathon and before you know it you are standing at the starting line of the NYC Marathon about to embark on a 26.2 mile expedition. Ooof. BEWARE. this may happen to you. The Apple Watch is the gateway device (drug) to running a marathon. Take that as you may.

Running Apps

Running apps from Nike Run Club, to Map my Run, to Strava, all provide analytics for runners that allow them to track training, set goals, and better understand their capabilities. Outside of the individual analytics, the social networking functionality has been the real innovation amongst the platforms. Strava in particular has become the creme de la creme of running apps, by way of its intuitive UI, strong social network capabilities, and level of detail surrounding its tracking/analytics. With over a 150 hours booked and ~1100 miles logged this past year, I have seen first hand the value of 1) building a circle of running interested friends on the app and 2) tracking performance over time.

The value of making the app social:

Learning. As a novice, you automatically get visibility into more experienced runners (friends) routines, pace, distances, etc. Learning from those further ahead in their running careers is a low effort and low cost way to build a routine that works for you.

Motivation/Accountability. Seeing your friends grind, motivates you too as well.

Connection. Running is inherently an individual sport, but doing it with others has a plethora of benefits. Using Strava as a spring board to run with others is a low friction way to find friends with similar running habits, paces and link with them IRL.

The value in activity tracking:

Training Insights When training for a marathon knowing the amount of millage logged each week is crucial in understanding how much more work is left to be done. Strava lets you log weekly millage to stay on track with your training plan, lets you more effectively plan your tapper, and also allows you to gauge the difficulty of runs at different paces. Comparing heart rates across similar runs is the most clear way to see progress ie: Running a 8:30 mile for 10 miles at a heart rate of 160 bpm a 8:30 mile vs. 10 miles at a heart rate of 145 bpm is a significant indicator of progress. This also allows you to set better informed goals…

Goals Setting: Once you have an understanding of where you stand with pace and the level of effort to sustain that pace for long distances you are able to set goals for marathon day. Being able to see your best effort 5k, 10k, 20k, runs allows you to put your pace in perspective, ultimately setting better informed goals for race day.

Strava, like the wearables category, is a tool that innovates by increasing access. It equips the average runner with the tools, analytics, content, and at some level a support system necessary to train for a marathon.

Fuel

Long distance running is a war of attrition. For the typical runner, within 90-120 minutes into an activity your body depletes the stored carbs (glycogen) to the point where it can no longer adequately supply the necessary working muscles with the fuel needed to produce energy. This results in your body taking drastic measures to slow you down. When the stored carbs are nearly finito, fatty acids step up to the plate to be burned as an alternative energy source for your body. The catch? Burning fatty acids requires significantly more oxygen, so your body forces you to slow you down as it needs sufficient oxygen to burn the fat used to fuel your activity.

How do you avoid this?

The better shape you are in the more glycogen you can store which allows you to prolong the time it takes for you to “hit the wall”.

You can use fuel while running.

Fuel can come in many forms, typically any simple carbohydrate fits the bill—they can come in the form of a liquid, gel, chew, bar or even just actual food. Ingesting anywhere from 30g-90g of simple carbohydrates per hour of activity lets you sustain high energy outputs for hours on end while running. A variety of energy specific simple carb consumables have entered the marathon scene as a form of fuel. They are specially formulated to be easy to digest, carbohydrate dense, and conveniently packaged. The fuel comes in the form of gels, goos, and gummy chews—all delivering fast carbs in a convenient and efficient ways, with some also providing electrolytes and caffeine for an added push while running.

Energy gels and chewables have been an innovation that has positively impacted both performance and access in marathon running as more runners are now able to run longer distances without “hitting the wall”.

Wrapping Up

Exploring innovation's impact on marathon running reveals a dynamic interplay between tradition and progress. From the primitive conditions of the 1904 St Louis Olympic Games, where runners faced unpaved roads and drank toxic concoctions, to the present day where super shoes, wearables, running apps, and energy gels redefine the sport for the masses while also elevating the performance of elite runners. The marathon has undergone a transformative journey over the last century aided greatly by the alchemy that is innovation.

Further Down the Rabbit Hole

Francisco Lázaro was a Portuguese Marathoner who died during the 1912 Olympics after greasing up his body for the race to avoid sweating (and perform better)

About the Ineos 1:59 Challenge

Hitting the Wall/Bonking during a marathon and how to avoid it

Technological Doping: The science of why Nike Alphaflys were banned from the Tokyo Olympics

A solid Thread on X about getting into long distance running