The Labor Corollary

Oh to chop wood with loving grace, toil, and strife

The Strenuous Life

In 1899 Theodore Roosevelt gave a speech titled A Strenuous Life before the Hamilton Club in Chicago. Among other things, he spoke galvanizingly when saying doing hard things is good, actually (albeit far more eloquently).

“I wish to preach, not the doctrine of ignoble ease, but the doctrine of the strenuous life, the life of toil and effort, of labor and strife; to preach that highest form of success which comes, not to the man who desires mere easy peace, but to the man who does not shrink from danger, from hardship, or from bitter toil, and who out of these wins the splendid ultimate triumph.” - Theodore Roosevelt

Much has happened since then, but today the mood has largely shifted to one preoccupied by instant gratification, shortcuts, and the word of the hour, slop. Meme coins, sports betting, and addictive social media algorithms have captured the zeitgeist, leaving the tech industry with a PR problem and society in maelstrom.

The Labor Corollary builds off Theodore Roosevelt’s 1899 speech A Strenuous Life and Will Manidis’ 2025 essay Craft is the Antidote of slop. A Strenuous Life contends toil is necessary and even good. Craft is the Antidote of Slop introduces the modern concept of “slop” and suggests it’s solution is craft. The Labor Corollary expands on these ideas.

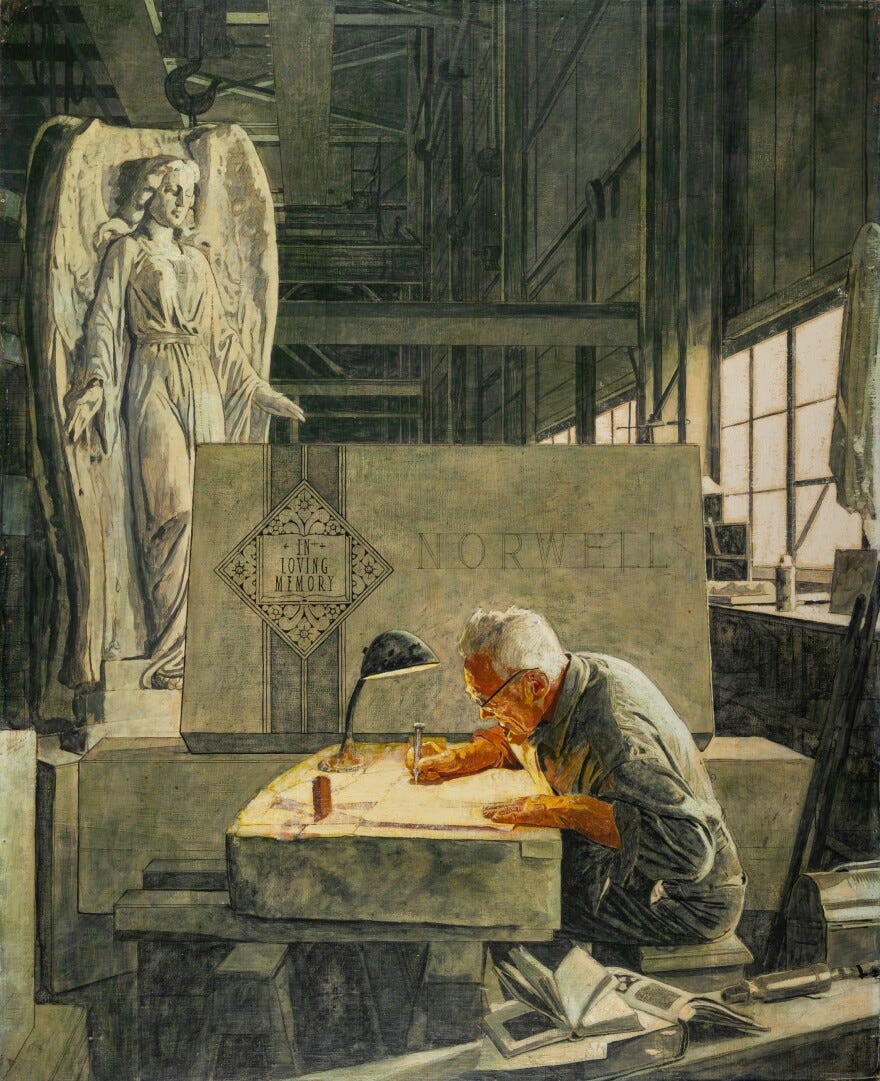

The Contemporary Craftsman

“A mere life of ease is not in the end a very satisfactory life, and, above all, it is a life which ultimately unfits those who follow it for serious work in the world.” - Theodore Roosevelt

The contemporary craftsmen approaches serious work in accordance with Roosevelt’s world view. He acts as a steward of past approaches, builds bespoke and hard to replicate things, and often leaves traces of imperfection in his work—the marks of genuine human contribution. It is easy to say a craftsman may have luddite tendencies, but in line with Mr. Roosevelt’s advice, I’ll take the path of greater toil. I’d argue, a true craftsmen yearns for ways to improve his craft and in turn the quality of his output. Technology, when wielded properly, has the potential to do both of those things. In fact, the craftsman actually cares quite deeply about his technology stack. He utilizes the right set of tools thoughtfully in service of a mission to produce better.

If quality is the craftsman’s north star and craft is the antidote to slop, then the craftsman becomes the physician administering that cure. This begs the question: what, then, is the industrialist?

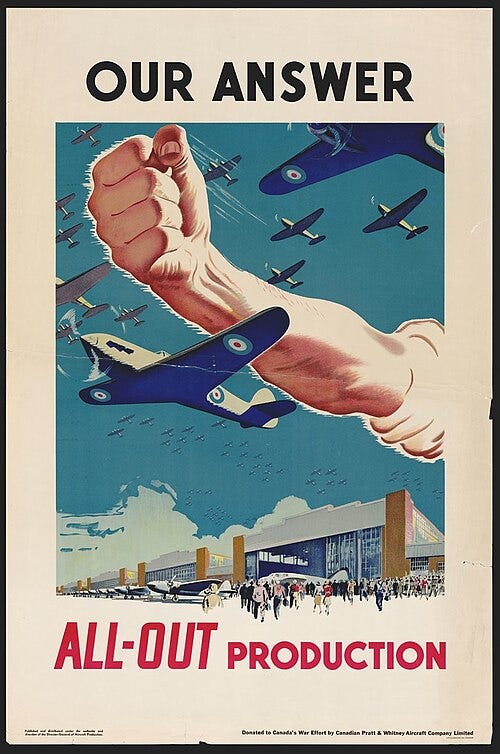

The Neo-Industrialist

The neo-industrialist is like the craftsman, in that they both produce. Both find meaning in participating in creation rather than mere consumption. Where they diverge is scale. The industrialist reveres scale of production and the craftsman revels in the intimacy that comes from limited production.

The neo-industrialist is singularly focused on production. He leverages technology not only at higher volumes than the craftsman, but also in different ways. The craftsman uses technology to improve his output, the industrialist uses technology to make processes more efficient and to increase production capacity. Higher volume and more efficient process leads to lower prices and greater availible output. If the contemporary craftsman builds for the individual, then the neo-industrialist builds for society.

Despite the ardent support of technology improvements to expand supply side production and process efficiency, the neo-industrialist still experiences toil. Industrial production, even when made hyper efficient with technology often takes an army, a team, to produce sufficient caliber output, at scale. The thing that unites both craftsmen and industrialists? Production by way of doing hard things. Even with technology, toil is the toll paid in pursuit of production.

Until now. Enter this new, other, third thing.

The Slop-Proprietor

“Slop emerges when we eliminate not just toil (the burdensome aspects of work) but labor itself (the meaningful human engagement with creation). Slop is production without history. Slop is detached from genuine human contribution. Slop born of effortless, replicable processes.” - Will Manidis

The slop-proprietor produces without labor. The strenuous life is non-existent — no toil, effort, labor or strife. Just production. Unlimited production.

Rather than using technology to make the output better in the case of the craftsman or process more efficient in the case of the industrialist, the slop-proprietor outsources process and output wholly. If the craftsman builds for the individual and the industrialist builds for society, this third thing builds for the sake of its proprietor, often at the expense of the individual and society.

Chopping Wood

If the human condition requires a life of toil and effort, of labor and strife to live a virtuous life then what happens in a world dominated by the slop-proprietor?

Perhaps the prevalence of the slop-proprietor decouples utility from labor. Like the commercial gym filled a void left by reduced physical work, meaningful labor becomes a chosen practice—something people seek not for survival, but for the sake of creation itself. Enter labor as leisure.

Alternatively, society may actively resist and constrain the slop-proprietor's reach, reasserting the primacy of labor in domains where it matters most.

“In this vision of redemptive labor, we can glimpse a more hopeful future where technology serves its highest purpose by eliminating true toil while preserving the sacred space for human hands and minds to engage in genuine craft. When automation frees us we gain capacity to redirect our energies toward the kinds of deeply human creative acts that build the Kingdom: tending gardens, raising cathedrals, composing hymns, and nurturing communities. It is a participation in the ongoing work of building the Kingdom.” - Will Manidis

To have a craftsman spirit is to love thy labor and care deeply about the inputs. But, society, at scale, cannot be powered by craftsmen alone. Industrialists are essential to reliably deliver the volume of output society requires. In their highest calling, the neo-industrialist labors to keep society alive; the contemporary craftsman labors to make life worth living.

Navigating this burgeoning third new thing will define the next decade for builders. In tech circles, “agency” was declared the only moat. Then came “taste.” What comes next remains unclear—but one thing is certain: In a world that acknowledges the slop proprietor, the most valuable capabilities accrue to those who spend time in toil, earning the tacit knowledge that uniquely can be found in labor.

After chopping wood for long enough, you know which cut will fit just right in the stove and which will burn through a long night. Oh to chop wood with loving grace, toil, and strife.

Inputs:

Recent readings that helped inspire this essay.

Fantastic essay on reclaiming meaningful labor in an age of automation. The distinction between craftsmen who use technology to improve output versus slop-proprietors who outsource everything is particularily sharp. I've noticed this in my own work where the most fullfilling projects always involve some element of struggle or constraint. When everything becomes frictionless, the satisfaction of creation seems to vanish entirely.